We echo what our valued colleague, Paul Forbes, Executive Director of Educational Equity, Anti-Bias & Diversity in the NYC DOE’s Office of Equity and Access, observes:

“We know what needs to be done. Do we have the will to do it?”

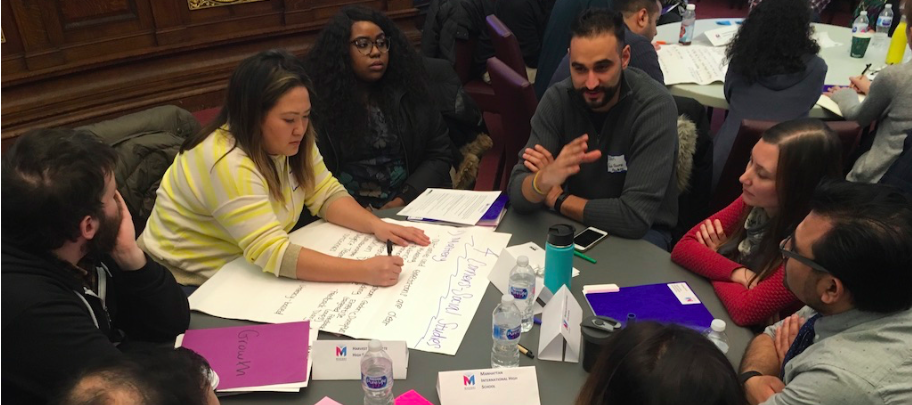

The MC provides community for leaders, educators, and students who possess that will. This kind of determination will be crucial for us as we dive deeper into the work. Moving toward more effective mastery-based and culturally responsive approaches is a complex and multidimensional process that is as challenging and confusing as it is joyful and inspiring. NYU’s research is focusing on the most powerful aspects of our model to ensure that whatever we find will help others generate the determination they need to continue to innovate and apply best practices known to enhance equity. In NYC, as we infuse mastery learning with culturally responsive practices, students tell us that this work is powerful and meaningful. (To hear their perspectives, check out this incredible video.) So, as our community awaits results of NYU’s study, we’d like to share a few observations now about working toward mastery-based, culturally-responsive approaches to education. Over the next several months, we plan to share more posts on this work with you here. For now:

1. This model works well for all students. Culturally responsive, mastery-based education is not a special initiative for traditionally underserved learners. This is not an extra support for students who are behind. This is not an exclusive opportunity for high-performing students. It’s just a powerful way to do school. It benefits different students in different ways. We have yet to encounter a school where learners don’t respond positively to this model.

For students of color, this approach can mean learning in an environment where one can experience being seen, valued, welcomed, supported, and held to exciting expectations. It also means students regularly engage teachers and school leaders who are willing to look at and work on their own beliefs, biases, and expectations, and strive to improve their cultural competency—the ability to be aware of one’s own cultural, social, racial identity and perspectives, and the ability to interact effectively with others who are not like yourself, however you define that difference. Students notice when their teachers are comfortable with them and believe in their potential—which is why we work as a community to look at our own beliefs, biases, and expectations—and to build our cultural competency, and our skills as growth mindset coaches.

For students who attend highly selective schools and tend to stress about grades, this approach offers an opportunity to focus more on learning and less on the competitive nature of 0-100 grading. (Is it really meaningful to give one student an 89 for 10 months of work, and another student a 91? What does that 2-point spread capture? The more you think about grades, the more apparent is the false objectivity they convey.) As student Georgios put it: “Instead of comparing grades—which we used to do before we had mastery—we are comparing our thoughts.”

For English learners, this system offers a way to develop mastery of discipline-specific learning outcomes and language acquisition outcomes, and clarity about both. “I’m a recent immigrant, so my grammar is not perfect. But I can still move ahead quickly in math and science,” said one student at MC Living Lab School Flushing International High School last month. Have a look at this language outcomes rubric to see how Flushing International High School makes clear the pathway toward English proficiency for English learners. Flushing International also has outcomes and rubrics for each discipline, and for the work habits that underpin success in all disciplines, plus the adults in the building share responsibility for teaching and coaching on all these outcomes. “If you’re a math teacher here, you’re still a language teacher,” says Principal Evangelista.

For students with an individualized education program (IEP), this approach can mean increased focus on growth and progress, and can clarify and support learning by naming and explicitly teaching habits, skills, and mindsets learners use to get traction in school. The flexibility to return over time to specific learning goals helps everyone, but our educators who work with students who have IEPs tell us this is especially valuable for those learners.

For students with learning gaps and misconceptions, a CRE/mastery approach supports positive learning identity and mindsets for learning, and also homes in on specific skills and understanding students need to build and master before they can move ahead. There’s also the advantage of flexible pacing; learners can spiral back to shore up what they still need to master, while moving forward on the aspects they are ready to engage afresh. When you get a 70 on the Unit 4 test in a traditional school, Unit 5 is likely to start Monday, with no clear plan to make up the 30% you have not yet mastered. Sal Khan’s nonpareil treatise on pacing and masterypoints out the considerable shortcomings of moving ahead while leaving learners and learning behind. His funny and apt house-building analogy starts: “We have two weeks to build a foundation. Do what you can!” A mastery approach—with its signature flexible pacing and actionable feedback—can be a curative and a preventative measure for gaps and misconceptions.

2. All schools are culturally responsive. The question is: to whom? It can be illuminating to reflect on the ironies in that claim and question. The Civil Rights movement was about removing access barriers to our culture’s institutions. As racial justice trainer and early childhood educator Megan Pamela Ruth Madison clarified for me during a training called “Talking About Race (and Mastery),” the work that remains undone is making those institutions equally welcoming and useful for all.

Given our country’s long history of racism, to go about educating children in a colorblind way is almost surely to reproduce racism—so we cannot do that. About 85% of students in NYC public schools identify as being of color. They are from hundreds of cultures and countries, speak dozens of languages, and come from a wide range of economic realities, as well. In NYC, about 60% of the teaching force is white. We find the precepts of cultural responsiveness to be a powerful student-centered framework for seeing, welcoming, and valuing the diversity across our beautiful city. So what is CRE? Let’s go to its founder for the basics. Here are Dr. Gloria Ladson-Billings’ three pillars of culturally responsive education (CRE), which are a touchstone for the MC’s work.

All students can, and must, experience academic success.

Students must have command of cultural competence: the ability to understand their own cultural identities and lenses, and to interact effectively with others who are very different, however each person defines that difference.

Students must develop critical consciousness, through which they challenge the status quo of the current social order. With support, students can turn awareness into power.

3. An explicit anti-racist stance is needed. Nationally, 80 to 90% of our teaching force is white, and just over half our students are people of color. This is factual, not news, and not to be avoided in polite discussion. In a society with a centuries-long history of racism, to operate from good intention without a racial justice lens and gameplan is almost certain to create conditions that reproduce oppression and inequity. Our community’s game plan: name race and racism, investigate and reflect on how race shows up, and on our nation’s racial history; role play and critique our efforts until we are more capable in our dealings with young people; hold sustained conversations about how race can play out in grading policies, classroom management, and curriculum design; seek to enrich our collective expertise by using as touchstones the work of leaders who are clear-eyed about race and education. The MC community has gained much from the work of The Center for Racial Justice in Education, Gloria Ladson-Billings, Zaretta Hammond, Django Paris, and others.

4. Transparency is a paramount value. Students’ learning goals and criteria for success should be shared from the outset—or co-created with learners. “Shared” does not mean “handed out.” Taking time to build shared understanding is crucial. We know school is a nonstop game of beat the clock, and teachers are rightly skeptical of time-consuming asks. And we know, because we have seen, the incredible power and value of dedicating instructional time to talking over learning goals and criteria for success. Taking time to establish this with learners is one of the most important value-adds of a mastery-based approach. It clarifies everything. It helps students learn how to learn. It ensures there’s no secret path that some students innately know but others never figure out. The time is definitely worth it.

5. Learning is a process undertaken by the learner. This was my 2018 mantra. It seems so basic, but it’s not how we generally proceed. As we lay out what we want students to learn, as we design units and lessons to make that happen, we need to be aware that what we are doing is creating a set of conditions for the most important thing to happen: learners learning. That is to say, the lesson plan or unit plan is there to serve a purpose, and is subservient to that purpose. We need to value students learning much more than we value “covering everything.” Deep conceptual learning requires processing time, what Zaretta Hammond calls “chewing.” We know there are ten or so revolutions that need to be covered in global history—but mastery-based teachers tell us that if you teach several of them thoroughly, students will transfer their understanding successfully and will be able to analyze historical events they have not encountered before. Deeper is better than faster, because that’s what makes learning sticky.